Budapest conference: Memory Politics in Comparative Perspective

The EuMePo (European Memory Politics) Jean Monnet Network conference was hosted magnificently by Ildikó Barna and her ELTE Research Center for Computational Social Science colleagues in Budapest from 14-16 June 2023. It was particularly exciting to hear from Ildikó and others of the rigorously empirical approaches being brought to memory studies at ELTE, involving the application of AI and other machine-assisted learning technologies, which allow scholars to analyze deep patterns in memory discourses—patterns that other approaches would surely fail to detect in the first place. In terms of substantive contributions, the conference demolished the received wisdom that Eastern and Central European countries diverge starkly and categorically from their North American and Western European counterparts when it comes to the contemporary politics of memory. First, we saw that in all of the countries under discussion there is a common trend of right-wing challenges to the liberal memory politics associated with the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the regretful memories of Holocaust and global catastrophe that produced it. Second, even where clear divergences in the contemporary politics of memory are found, these divergences often involve conflicts and nuances internal to the so-called East and West rather than patterns setting two regions or camps distinctly apart.

Kate Korycki (Western University, Canada) set the tone on the Konrad Adenauer Foundation Canada Panel (video link) by emphasizing the common mobilization of far-right actors in North America and Western, Central, and Eastern Europe around nostalgic populist nationalism. In countries such as Hungary, Poland, Canada, and the United States, right-wing memory entrepreneurs peddle stories of national greatness threatened by liberal political correctness as a salve for and distraction from neoliberalism’s corrosive stress on austerity, competition, and constant self-improvement. Unable or unwilling to offer meaningful material redress, let alone structural change to neoliberal forces and patterns, the far right targets liberal memory politics instead, attacking critical engagement with national histories of racism, antisemitism, and state cruelty as the “cultural Marxism” of cosmopolitan elites.

Yet Piotr Oleksy (Adam Mickiewicz University, Poland) also reminded us that this broad path of convergence is strewn with all manner of important national differences. Certainly, the Polish right’s rejection of liberal, post-Holocaust “never again” memory politics reflects a more widely shared discomfort with what many in Central and Eastern Europe see as an alien memory regime. That memory regime was, after all, created without the participation of post-Communist countries and, as the belated Western European and North American realization of Putin’s designs on Ukraine arguably showed, was not a helpful source of alertness to Putin’s revived Russian imperialist agenda. Yet this broad context of post-Communist mnemonic convergence has not produced anything resembling a monolithic response. For example, although the Orban government shares the Polish right’s rejection of the postwar liberal memory model, its own calculations about geopolitics and domestic support led it to a quite different stance on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Furthermore, as Oliver Schmidtke (University of Victoria, Canada) reported, even as the Western memory culture’s lack of vigilance against Russian revanchism provides a “we told you so” rallying cry for many, support for EU membership remains strong across Eastern and Central Europe, regardless of different national stances on the war in Ukraine.

Further mnemonic divergences in Central and Eastern Europe arise from specific differences in regional or national post-communist transitions. For example, Karolina Lendák-Kabók (ELTE Faculty of Social Sciences, Hungary) showed that the Balkan wars of the 1990s greatly intensified the dislocation of transition for a “shocked generation,” whose fathers were forced into military service and who then found themselves contending for decades afterwards with the hardening and intensifying of various cleavages that had been activated by the conflicts. Existing post-WWII or post-communist mnemonic repertoires would seem to offer little guidance for navigating these particularly harsh experiences. Indeed, speaking of Jewish refugee survivors in postwar Poland, Lidia Zessin-Jurek (Masaryk Institute and Archives, Czech Academy of Sciences) helped push this emphasis further by emphasizing that individuals coping with post-genocidal dislocation and trauma necessarily do so within complex national and even local ecologies of memory that entail distinctive micro-level processes of negotiation and adaptation.

Notwithstanding these divergences in political responses, international allegiances, and mnemonic orientations, there seems a shared need to find better ways of responding to far-right attacks on the interrelated practices of regretful memory and democratic politics. After all, the “affective polarization” around national identity and memory noted by Domonkos Sik (ELTE Faculty of Social Sciences, Hungary) in the Hungarian case is a problem in other contexts, and Sik’s prescription seems more widely applicable as well: we need new approaches to memories of injustice that can help to shore up democratic allegiances and norms in adverse times. Indeed, Andrea Petö’s (Central European University, Austria) argument seems particularly important in this regard: it may be almost insuperably difficult to challenge the memory politics of the far right in the context of an international academic prestige system that gives scholars strong incentives for participating in English-language debates in venues that are removed from and often uninterested in the political spaces of greatest importance for the most affected.

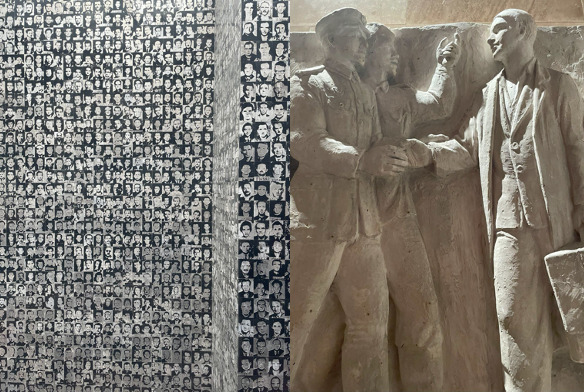

The challenge of revitalizing democratic memory politics in tough times is a generational one as well. For example, reporting on their work in youth-focused memory politics education, Beate Schmidtke and Kästle Van Der Meer (University of Victoria, Canada) explained that there is a particularly pressing need for new, more experiential, more resonantly immediate, and less academically didactic approaches to memory politics education at a time when injustice memories are fraying and direct survivors fewer to be found. Youth-produced materials, such as the “Using the Past to Define the Present” booklet, offer one crucial way forward. Experiential learning, such as the Memory Politics 2023 Study Tour that brought our group to Europe, is another. And yet at another level, some challenges of democratic memory politics will remain the same. Speaking specifically of Holocaust education, Janine Wulz (University of Victoria, Canada) stressed the continual need to balance equally and creatively among cultural, ethical, historical, and analytical approaches. For her part, Elke Rajal (University of Passau, Germany) added a further balancing consideration to the mix: democratic memory politics education must focus equally on matters of trauma and survivor experience, on the one hand, and questions of perpetration, responsibility, and the causes of gross injustice, on the other.

Matt James, Department of Political Science, University of Victoria