Vienna: Stumble upon memory

In 2014, I heard about Stolpersteine for the first time. In a course about Sites of Memory and Conscience at the University of São Paulo, I learned that these stumbling stones – their literal translation – are brass plates on concrete cubes that commemorate victims of the Holocaust. In 1992, the German artist Gunter Demnig started to design these small memorials to be set into the sidewalks outside those people’s last-known freely chosen residence or workplace. There are more than 70,000 Stolpersteine across Europe, and I was happy to stumble upon two of them while walking in Vienna during the study tour in memory politics!

Noticing a plaque on the pavement, one must stop their way and bow to read the information, a physical movement that interrupts the flow of the present to connect one to the past. A few blocks from our hostel in Favorite, a plaque remembers that Janka Löwestein and Simon and Risa Steiner lived at 5 Ettenreichgasse until 1942, when the Nazi regime deported them to Izbica. While informing us how they were murdered, this memorial is also evidence of life: it enables us to imagine them living in that house and having a regular routine like the hundreds of people who pass in front of their residence every day.

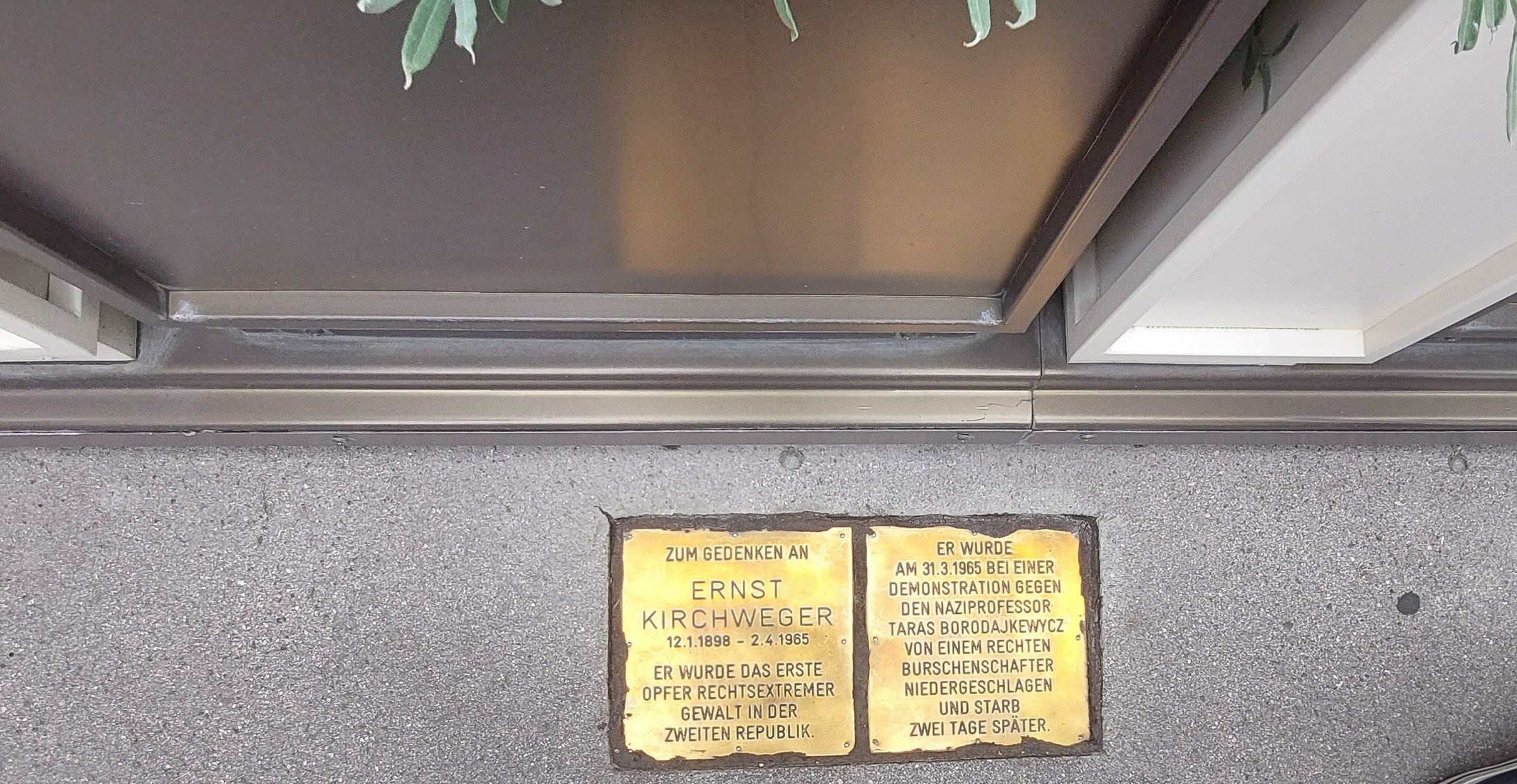

Outside Café Sacher Wien and facing the Opera House, a famous plaque remembers Ernst Kirchweger. Unlike most stolpersteine, this memorial commemorates the first victim of far-right violence in the Second Austrian Republic in 1965. Kirchweger was an activist and Holocaust survivor murdered in the demonstrations against Taras Borodajkwycz. He was a former Nazi Party member and professor at theVienna University of Economics and Business who openly expressed his antisemitic and fascist views. In this way, this stone is a reminder that even though there was progress in human rights, authoritarianism also survived the war, and we need to discuss its manifestations in post-1945 democracies.

Source: Defensoría del Pueblo – Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires:

I was also always fascinated by how the meaning of this memory project crossed oceans and inspired other societies to translate their wishes for remembrance in their territories. In Argentina, for example, the collective Barrios por la Memoria y Justicia (Neighborhoods for Memory and Justice) created the initiative Baldosas por la Memoria (Tiles for Memory) to remember victims of killing and forced disappearance during the military dictatorship (1976-1983). Groups of neighbours in different parts of the city started to research and mark victims’ houses, schools, and workplaces, as well as the places where repression agents kidnapped the opponents. The plaques usually have a painted background, and small colourful ceramic pieces frame personal information about the victims, such as their name, their role as popular militants and the day of the disappearance by state terrorism. However, unlike the stolpersteine, the baldosas do not follow a strict shape and material pattern: produced by different neighbourhoods, they express the diversity of the territories where the victims and their neighbours are from.

The artist Demnig’s motto for the Stolpersteine is, “A person will only be forgotten forever if their name is forgotten.” Whether in Vienna or Buenos Aires, their memories are alive.

Ana Paula Santana Bertho, MA Candidate in History at the University of Victoria