Reflecting on Evidence of Life

Throughout the Study Tour in European Memory Politics, our group learned many details about the Holocaust. We have learned shocking statistics, like how in Krakow our guide explained to us that before the war, one in four people in Poland were Jewish, and now, in the city of Krakow, the orthodox Jewish community has around a hundred members. At Auschwitz, we heard details of executions and torture, we saw piles of empty cyanide containers and demolished gas chambers, bombed by the Nazis to hide evidence of their crimes.

However, the things that have had the deepest emotional impact are not evidences of the mass murders committed, but rather, the evidences of life. Seeing the Jewish neighbourhood in Krakow, a place of Jewish life that is one of the few to not have been destroyed during the war served as a reminder of the lives that were built and being lived before the mass murders of the Holocaust. Now, in the Jewish cemetery, walls have been built out of destroyed Jewish gravestones by survivors, who had to rebuild their fragmented communities even after so many of their loved ones had been lost.

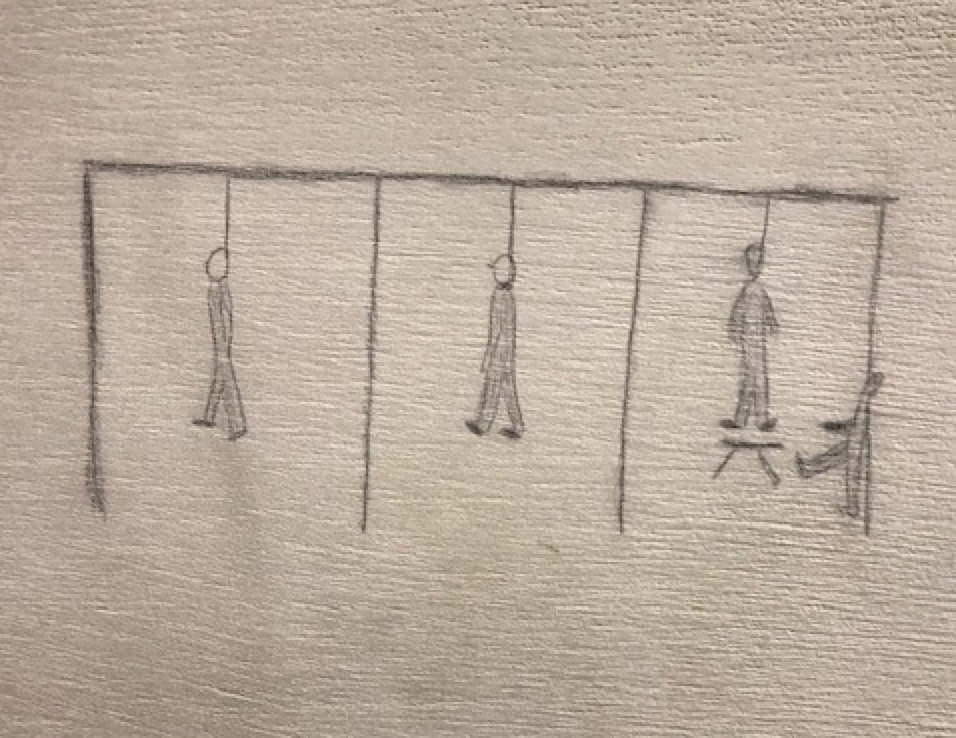

I felt the emotional impact of this evidence of life most strongly at Auschwitz. There is a room there full of human hair that was shaved from the heads of 30-40,000 women. In that room, I instinctively touched my own hair, and felt deeply nauseous. Rooms of personal belongings, such as baby clothes and shoes, deepened this sickened feeling I had. In the Yad Vashem exhibit, videos of life before the war played on screens before we entered a room full of recreations of drawings done by Jewish children. I wept all throughout the exhibit. When the guide told us that the Nazi officer who ran the camp lived with his five children nearby, I tried to wrap my head around how someone could torture children and then return to his own, and it hit me that he would not have seen the prisoners as human, like his children, at all. At the Austrian Museum of resistance, we learned that many Nazi perpetrators never went to trial for their crimes. Many changed their names and fled to continue living their lives.

For many of us, we first learn about the Holocaust in terms of Nazis and Jews. I think what is so powerful about seeing and experiencing evidence of life is it reminds us that both groups are human. The Holocaust was not something simply done by Nazis to Jews, but by humans to other humans. Those who died in the Holocaust were people, who lived their lives, just as we do, and who suffered greatly and died at the hands of other people, who also had lives like ours, who were just as capable about caring, as we do, as they were capable of hatred, like we could be. When we think of the phrase of “Never Again” in terms of the Holocaust, we must reflect on what that truly means, as human beings who have to share this planet with other human beings.

Maia Vasko is a third year student attending the University of Victoria. She is double majoring in History and Pacific and Asian studies and especially interested in broadening her knowledge of contemporary European memory politics during the Study Tour in European Memory Politics.